Taipei, Taiwan — It is Jamie Wang’s headline show at Taipei’s Two Three Comedy and the audience loves her. She has been doing standup sets at shows and open-mic nights here for a year.

Tonight, she is wearing a pink minidress with knee-high white boots, her eyeshadow glittering under the spotlight. She gives a dry delivery of sex jokes — and anecdotes about what it’s like to be a Chinese citizen in Taiwan.

“The most common question I get is like, ‘do you know there is no democracy in China?’ No s***, Sherlock,” she says as the crowd erupts with laughter. “I think it’s quite a mean question because I can feel that they don’t really want an answer from me, they just want to point that out for me. It’s kind of like asking an orphan, ‘do you know you don’t have parents?’”

Wang has been living in Taipei on and off for nearly seven years, working towards a Master’s degree in philosophy at National Taiwan University (NTU). But he says he is most comfortable in crowds like this one, at the comedy club, where the audience is mostly made up of foreigners.

“I mostly just hang out with international students, they don’t really care where you come from,” she said.

Wang is one of a dwindling number of Chinese students — known in Chinese as Lusheng — who remains in Taiwan. In 2020, the Chinese government announced a ban on new degree applicants to Taiwanese universities and three years later, the last cohort of bachelor’s students from China is about to graduate.

Even as tourism and educational exchanges begin to reopen between China and other countries around the world, exchanges with its neighbors roughly 160km (100 miles) away across the strait are in sharp decline. Many lusheng feel like the collateral damage of worsening Beijing-Taipei ties, given the brush-off by politicians on both sides of the strait.

“This new situation is very much like the situation we had during the cold war when there was no people-to-people exchange,” said Tso Chen-dong, a professor of political science at NTU and a former director of the Kuomintang’s Mainland Affairs Department.

In recent years, exchanges have become “unidirectional,” Tso said. “We cannot have direct contact with mainland people if they don’t come to Taiwan, and it’s very difficult to build friendship without in-person contact.”

Rather than a side effect of COVID-19, politics was the main motivation for China’s ban — a kind of punishment after President Tsai Ing-wen of Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was elected to a second term in a landslide.

The DPP advocates for Taiwan’s self-determination and is seen by Beijing as a threat to its claimed sovereignty over the island.

Exchange in decline

Cross-strait educational exchange first began in 2011 under President Ma Ying-jeou, who aimed to cultivate closer economic ties with the mainland.

In 2011, 12,155 short-term and degree students came to Taiwan from China to study. By 2016, that number had reached 41,975.

That year, Tsai won her first presidential election.

The DPP was opposed to the policy and skeptical of mainland students, said Lin Hsien-Ming, an assistant professor at National Pingtung University’s Teacher Training Center.

Mainland students like Wang are not eligible for national health insurance or government scholarships, or allowed to work to supplement their studies, unlike other international students.

“This is a kind of discrimination against the mainland Chinese students. But behind this discrimination, it’s about the fear of our national security.” Lin said.

But China also began restricting the number of students allowed to study at Taiwanese universities in the year Tsai was elected. A report by Singapore-based Initium Media found that counties in Taiwan’s south, which tended to vote for DPP candidates, were most badly affected by the curbs.

By 2019, the total number of lusheng had already declined by 40%.

In 2020, most mainland students became stranded at home in China while Taiwan’s border remained closed to returning students. They were not allowed to return until months after students from other “lower risk” countries.

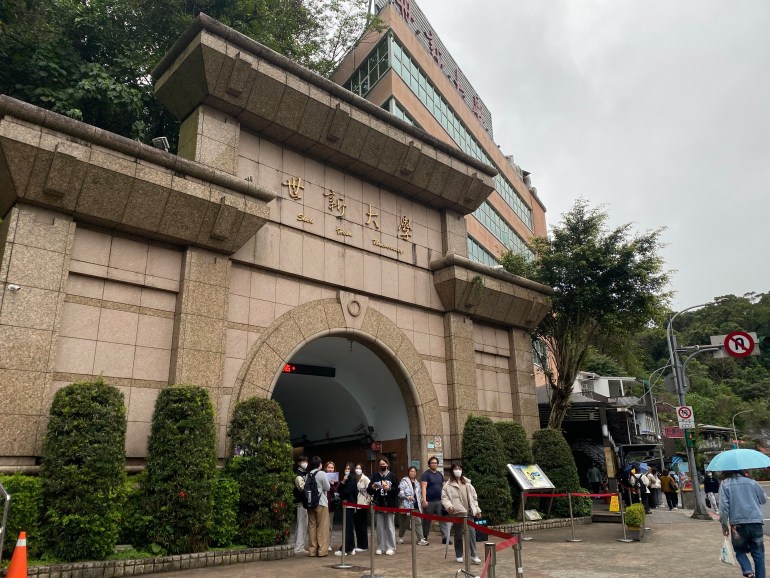

“I think both sides have responsibility because the DPP and CCP [Chinese Communist Party] don’t like each other. But I think Taiwan went too far during COVID-19, especially when targeting Chinese students,” said Li Gongqin, vice president of Shih Hsin University in Taipei, which once hosted about 800 Chinese students at its peak. Today, only about 80 remain, mostly degree students who will graduate this year.

Just more than 3,000 lusheng were left in Taiwan in 2022, according to government statistics. Only 22 of them were short-term exchange students, who once outnumbered degree students and were an important source of revenue for universities.

Allowing Chinese students to study in Taiwan once filled thousands of empty seats at universities suffering from a shortage of domestic students.

Now some, particularly the private universities, are suffering, said Nathan Liu, executive director of international education and exchange at Ming Chuan University. Universities have been looking to Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and Indonesia to fill the financial gap left by Chinese students, as encouraged by Tsai’s New Southbound Policy, an initiative with the goal of reducing its reliance on China and further integrating Taiwan into the wider region through economic and educational initiatives.

Ma Xiaoguang, a spokesperson for Beijing’s Taiwan Affairs Office, blames the self-ruled island for the situation, sidestepping Beijing’s own ban on Taiwanese students to claim Taiwan is discouraging Chinese applicants from studying there.

“Since the DPP came to power, it has practically destroyed the development of peaceful cross-strait relations,” Ma said at a press conference in January. “The turmoil of ‘Taiwan independence’ has permeated Taiwan’s campuses and discouraged mainland parents and students. If there are no students on the island, it is clear who is responsible.”

In response to an inquiry from Al Jazeera, Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council dismissed such allegations.

“The government’s position and policy of welcoming mainland students to study and exchange in Taiwan is consistent, and it also supports normal, healthy and orderly academic and educational exchanges between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait,” the council wrote in a statement. “Since 2011, mainland students have been allowed to come to Taiwan to learn and experience Taiwan’s free style of study and pluralistic and democratic way of life.”

Some Chinese students have taken advantage of Taiwan’s vibrant civil society more than others, such as Cai Boyi, a Chinese student who studied at Tamkang University and was active in movements such as the Sunflower Movement, a 2014 student-led grouping that protested against a proposed trade agreement with China.

Fan, a Chinese student who wishes to remain anonymous for her safety, has been living in Taiwan for more than four years. She said she knew a little about Taiwan’s politics before moving to the island to study: “at the time I didn’t know [Taiwanese people] don’t think we are in the same country,” she said. She now describes her views as postnational and has taken part in demonstrations in solidarity with LGBTQ+ people, China’s white paper protests, Ukraine, Myanmar, and Hong Kong.

Some high-profile cases of campus censorship and suspected espionage have raised concerns about the influence of Chinese students.

In 2019, some Hong Kong students were harassed by Chinese students for showing solidarity during the 2019 pro-democracy protests. But such cases are rare, and experts say that student exchange poses little threat to Taiwan’s national security.

“When students come from China to live in Taiwan, they actually get a real sense of Taiwanese society and politics that I think is otherwise difficult to achieve. So I think that is kind of a loss,” said James Lin, an assistant professor and historian of Taiwan at the University of Washington. “The obstacles to cross-strait educational exchanges for political reasons are perhaps a little bit short-sighted.”

Education and tourism are unlikely to be restored “unless there might be a different presidential administration after Tsai Ing-wen’s second presidential term ends,” Lin said.

Still, Chinese students have not completely disappeared from Taiwan. And recent actions by the Tsai government and Kuomintang party leaders — including reopening to Hong Kong and Macau — suggest both sides are interested in improving the relationship.

“This potential for cooperation is still there regardless of the fact that Ma Xiaoguang is using very strong language,” said Liu of Ming Chuan University. He said 12 short-term exchange students from five different universities in China arrived in Taiwan in February. “Personally I believe that the policy is still trying to maintain cooperation across the Taiwan Strait.”

Not a permanent home

For many Chinese students, Taiwan is just a jumping-off point for other opportunities outside of Asia. Many do not want to go back to China — it is too hard to find a job these days — so they hope to move to the United States, United Kingdom, or Europe for work or further study.

“I guess I wouldn’t mind staying in Taiwan, but I cannot,” said Wang, the philosophy student from NTU. “There’s no way [to stay] unless we get married or something.” She plans to go to the UK to pursue her comedy career.

For some students, Taiwan’s strict policies for mainlanders discourage them from staying longer on the island, even if they want to.

Fan has earned a Master’s degree at National Taiwan University and looked forward to continuing her studies in Taiwan, but has decided to pursue a PhD elsewhere because her inability to work while studying has burdened her family.

“When I apply to US programs, I am a little nervous because I don’t have [teaching] experience. I don’t know how that will affect my application. I even thought about doing some teaching assistant work without getting paid, just to get the experience, but my professor said ‘we definitely can’t let you work for free’,” Fan said.

Many Chinese students, curious about Taiwan’s civil society and culture, still want to come to study here, fans insist. And many, like her, would like to stay longer but cannot.

“It’s not just about political matters. It’s also the economy, and the labor market is so terrible [in China] recently. We saw some of our friends go back to China in the last two years. They are really struggling in finding a job and adjusting to life and social culture in China.”

Some of Fan’s friends have even considered changing their nationality one day so they can come back to Taiwan, she said. Fans have thought about doing the same.

“Even though [education] is a small thing, I think it’s very important. And I personally hope these things can continue to happen,” she said.